|

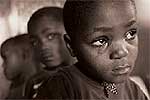

These three AIDS orphans in Zambia are among 10 million children left vulnerable worldwide. AIDS orphans a child about every 14 seconds. |

Someone's got to give

THE OCTOBER MEETING OF THE WORLD BANK and International Monetary Fund in Washington attracted only a forlorn handful of protesters and little notice from the rest of us. It was a poor showing on behalf of the world's poor, who these days could really use a little more attention. As a world of suffering piled up with poverty, refugees, and genocide last year, the U.S. committed more than $700 billion to military and security spending. The Iraq debacle and the War on Terror have proved a terrible distraction from the war on human deprivation.

At the World Bank meeting there was, as in years past, much talk about how the bank could alleviate the suffering of the estimated 2.7 billion people who live on less than $2 a day on this planet. But after seven decades of trying and failing to resolve the dilemma of widespread global deprivation, it's fair to wonder if the WB and IMF are only doing their real jobs too well—that is, to watch out for the best interests of the world's well-off, maintain good economic global order, and make a convincing feint at actually doing something about the unspeakable misery of the majority of the planet's people.

That's not to say that no good ever comes of WB summits. This year new agreements were reached to reduce the debt of some of the world's poorest nations. That will mean more money for health care, education, and clean water.

But even substantial debt forgiveness may prove a short-term fix as long as the racket of corrupt borrowing and outright theft that passes itself off as the international credit system continues. It's likely that before long many nations freed of their current interest burden will just assume new debt. What's really wanted is a "reform,' not of the World Bank or international finance, but of how people in the developed world think about global wealth and how it is distributed.

To that end, the church has an unpleasant message for us in the overly affluent world, one worth listening to in this season of peace and family unity, one that reminds us that real peace has to be earned through work and sacrifice and that the unity we are called to embraces our brothers and sisters all over the world, not just across our streets.

While we prattle on about reforming economic structures or new free-market strategies for poverty reduction, there is a much simpler explanation for the economic and political imbalances in the world: plain old sin, simple selfishness. Can one country that comprises 6 percent of the world's population, claims as much as half of its wealth, absorbs more than 30 percent of its resources, and exhales 36 percent of its waste continue blithely into the future as if there were nothing out of balance with its position in the world?

Surveying a ravaged planet in the aftermath of World War II, George Kennan, the hoary godfather of American political theory, answered, "Yes, and here's how.'

"We have about 60 percent of the world's wealth but only 6.3 percent of its population. In this situation we cannot fail to be the object of envy and resentment,' Kennan famously noted in 1948. America's "real task' in the future was "to devise a pattern of relationships which will permit us to maintain this position of disparity' and to desist with the "luxury of altruism and world benefaction.' Kennan's cold-blooded vision has been a part of U.S. strategic thinking ever since, a recipe for a fortress world of haves, holding out against the moral, rhetorical, or finally guerrilla assaults of the have-nots. It does not have to be that way.

As we approach the World Day of Peace on January 1 (its theme: "Do not be conquered by evil but conquer evil with good'), the church calls us not to be the fearful haves of the world but to use what we have for the good of all. A world of want and suffering will never be a world of peace, the world we are called to co-create. Building that world is not a spiritual exercise, it is, as President Bush might say, hard work.

It's hard work that requires personal sacrifice, clear thinking, and practical policy that, as Pope John Paul II said in a recent homily, must take into account "the numerous social and economic problems that weigh on the lives of peoples: inequalities, privations of all sorts, injustices and insecurity.'

Peace is not an event, it's a process that requires commitment and creativity. So live humbly, give freely, seek justice. It's the best hard work in the world that we can do.

Kevin Clarke is a senior editor at U.S. Catholic and managing editor of online products at Claretian Publications.This article appeared in the December 2004 (Volume 69, Number 12) issue of U.S. Catholic.

All active news articles