Visitation rites

Corporal Works of Mercy:

How Catholics find creative ways to make the Word flesh

Jesus was very specific about what he would like his followers to do with those in prison: "I was in prison and you came to visit me" (Matthew 25:36). The fifth in a series on the Corporal Works of Mercy, U.S. Catholic looks at how Christians act on this directive.

CONVICTED CRIMINALS rarely inspire much compassion. They are, after all, the people who actually do the things we have nightmares about—armed robbery, rape, murder. We want these people put away, sometimes for good. Isn't it what they deserve?

Criminals may deserve many things, says the Catholic Church, but vengeance is not one of them. "We are concerned because we sense in our society a growing acceptance of revenge as a principle of justice," writes Archbishop Harry J. Flynn of St. Paul and Minneapolis in his 1996 pastoral letter Church Teaches That All Life Is Valuable. "We who claim to be followers of Jesus need to search out the roots and reasons for our current attitudes about punishment for offenders. We must ask ourselves whether or not the negative power of vengeance has found a home in our hearts rather than the life-giving gospel of Jesus Christ."

|

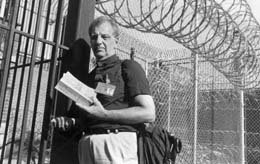

Deacon George Brooks waits outside Cook County Jail. |

A glance at church prison ministry in the United States reveals that "visiting the prisoner" takes many forms. Some people go into prisons and form friendships with the men and women there. Many write letters to prisoners they've never met. Some help prisoners continue their education in prison, while others train them for jobs. One group in Illinois brings tape recorders and children's books to mothers in prison so their children back home can hear their mothers read them a bedtime story and say, "I love you, honey."

Some people take on the task of watching pending legislation and organizing letter-writing campaigns on important bills. And some, like Sister Helen Prejean, C.S.J. of Dead Man Walking fame, speak tirelessly on the issue of capital punishment, swimming against the tide of "tough-on-crime" political rhetoric and reminding audiences that members of a "prolife" church have no business cheering on the state as it executes its people. "Prolife," says Prejean, "most often means pro-innocent-life, not pro-guilty-life."

In his encyclical The Gospel of Life issued March 25, 1995, Pope John Paul II acknowledges the necessity of imprisonment for people who threaten to tear the fabric of society. But here's what he has to say about capital punishment: "The nature and extent of the punishment must be carefully evaluated and decided upon," the pope writes, "and ought not go to the extreme of executing the offender except in cases of absolute necessity: in other words, when it would not be possible otherwise to defend society. Today, however, as a result of steady improvements in the organization of the penal system, such cases are very rare, if not practically nonexistent." The Catechism of the Catholic Church was recently revised to reflect this strong stance by the pope against capital punishment.

"Restorative justice, that's the key," says Sister Pat Davis, a Catholic nun who coordinates ministries to women in prison for Lutheran Social Services of Illinois."Restorative justice means we have three tasks as Christians. Number one, we must be supportive of the victims of crime and their families. Number two, we have to support the offender and the offender's family, who are often forgotten entirely. The offender must be given the opportunity to give something back to the community that he or she has harmed and also be encouraged to take responsibility for his or her actions. And number three, we have to look at ourselves as a society to see where we've all been wounded because of crime and try to bring healing. The community is, on the one hand, the offender by allowing horrible conditions for so many of its people, and, on the other hand, the community is also the victim."

The following sketches show just a few of the ways that today's followers of Jesus are heeding his advice to visit him in prison.

Somebody who cares

The accused who populate Cook County Jail come from some of Chicago's toughest neighborhoods, where drugs and death are more prevalent than trees and two-parent homes. Their backgrounds often have been so barren of love and guidance that they survive almost on instinct, which sometimes leads to the tragic circumstances that land them in trouble with the law.

Because of that lifelong affection deficit, though, many embrace any offering of friendship and support in jail with as much fervor as they did drugs and violence on the street. "I've just been overwhelmed with the problems they've had in their lives," says Deacon George Brooks, chaplain at Cook County Jail, "and in their willingness to be open and loving and caring." Those are traits seldom associated with the people who crowd the jail, a misconception that Brooks considers a contributing factor to society's tendency to shun them. "People just envision these wild, savage, crazy men," he says. "There is a built-in fear."

Brooks has no fear in jail. Only friends. He cried when one longtime inmate left, sentenced to life without parole for murder. And he felt physically ill for three days when he tried, successfully, to prevent another admitted murderer from receiving a death sentence. "Some of these guys are my best friends," Brooks says.

Although the jail is ostensibly a temporary holding place for the accused to await trial, the clogged judicial system often turns "temporarily" into four, five, even six years—more than enough time for deep, lasting relationships to develop between Brooks and the men behind bars.

|

Brooks conducts a prayer service in Cook County Jail's protective custody tier. |

The apparent irony of a religious person becoming a friend—not just another authority figure—to a group of men accused of murder, rape, and robbery does not surprise Brooks, who has met many who are deeply faithful, yearning for some guidance to bring out those feelings. "I am not a missionary going into some pagan territory to convert the pagans," Brooks says. "Many of them have had strong faith experiences, and they have gone astray or they haven't pursued their faith. Many have been disillusioned by clergy, or they've just ignored them."

They do not ignore Brooks, who makes daily rounds of the multi-tiered cell block, carrying on conversations or leading Bible studies or simply providing the one thing that Brooks says has been missing for most of their lives: "Somebody who cares about them."

Chauffeurs "R" Us

When you're 3 years old and Mom lives in prison two hours away and you don't have a car yet (except the Matchbox kind), you are in need of a friend. A friend with wheels. A friend who will show up at your house every week or every month to take you to see your mom so you can climb up on her lap and give her a hug and remember what her kiss feels like. You need someone like Mike Bennett, who for five years has been driving six kids (plus Grandma) to see their mother every couple of months.

The Family Connections program of Lutheran Social Services of Illinois matched up Bennett and his big Chevy Astro van with this large family who needed to visit Mom in Dwight Correctional Center, 75 miles from Chicago. He arranges a date—often a complicated business because the family currently has no phone service—picks up the family, and drives them to the prison. He usually reads a book or has a snack while they visit, then drives them back home.

"Sometimes we talk about whether it was a good visit," says Bennett. "A few times the mother appeared in manacles because of a disciplinary problem. At the end of those visits, the family was always very low. It's not fun seeing your mother or your daughter in chains. Now we try to check in advance to make sure she's not having a disciplinary problem before we go."

Over the months Bennett learned that the mother was sent to prison for murder. "I try not to be nosy or pushy," he says. Sometimes the grandmother will share the difficulties she faces raising the children in stark poverty. "Things are not very good at home right now. Two of the boys are in trouble, and Grandma's really in the dumps. It just shows me that even if you're trying to do something helpful, everything doesn't always work out."

Family Connections drivers took more than 1,000 Illinois children to see their mothers last year, says coordinator Sister Pat Davis. Seventy-five volunteers drove throughout the year.

"Jesus said to visit people in prison," says Bennett. "I don't know anyone in prison, but I figured that this was a way I could be obedient to that without waiting for someone I know to go to prison.

"I hope it's some motivation for the mother to be released as early as possible to be with her kids. And I hope the kids are reminded that their mother is there, she still loves them, she didn't go off and desert them. I hope it's some motivation to reach adulthood safe and sound rather than falling prey to gangs, delinquency, and violence."

Susan Berchiolli began driving out of a sense that "I have gifts beyond measure—an embarrassment of riches. When you're given much, much is required. I can't keep what I've got—I have to give it away."

Each week for four years, Berchiolli drove a baby boy to see his mother in prison. The child's grandmother refused to visit because she had a bad relationship with her daughter, so Susan drove him to Mom. Then the boy and his grandmother were killed in a house fire. "It just shattered me, because I had seen this boy every week for four years." She hasn't driven regularly since then, but her involvement hasn't ended. She became an unofficial advocate for the boy's mother when she was released from prison.

"Prisoners need someone on the outside who knows the ropes," she says. Because the woman's records had been destroyed in the fire, Berchiolli accompanied her to get another Social Security card. "They make everything so difficult. I got feisty and started throwing my weight around, but I don't know what she would have done if I hadn't been there.

"It's impossible to be part of this and not get involved with people's lives," she says.

Helping him into heaven

Brother Patrick Byrd's soft Southern accent sounds like it could diffuse a bomb, an appropriate trait for a man with his capacity to pacify.

He pacifies people who preach vengeance against violent criminals, urging them to put aside their hatred and see the humanity beneath the hardened exterior. "Regardless of what they've done," Byrd says, "they're still human."

And he pacifies the prisoners themselves, often despairing to the point of self-destruction in the emotionally deadening environment of death row. "Many of these men have lost all contact with their families. They are in a six-by-nine cell for 23 hours a day," Byrd says. "In that type of situation, you can lose touch with reality very quickly. It seems like there are increasing numbers of inmates suffering from depression who are giving up their appeals and asking to be executed."

He first witnessed the soul-stripping power of the prison system a decade ago during frequent visits to a friend convicted of murder in Louisiana. Determined to do something to help the thousands of forgotten men behind bars, he contacted Rachel Gross of the Death Row Support Project, based in Liberty Mills, Indiana.

From Little Flower Parish in San Antonio, Byrd now coordinates a program that provides pen pals—and hope—forprisoners around the country. Byrd himself corresponded for nine years with Larry Lonchar of Georgia until his execution in 1996, witnessing firsthand the transforming power of compassion that Byrd believes helped to change Lonchar's attitude toward God and earn him a place in heaven.

"He had a lot of anger toward Christianity," Byrd says. "The judge who sentenced him was a Protestant deacon, and he just couldn't understand how the judge could be a Christian and want to kill him."

But Byrd believes his actions, more than any Bible verse or sermon, changed Lonchar's perception of Christianity and helped him make peace with God before his execution. "I wasn't preaching to him—of course, I didn't miss an opportunity either—but my caring about him showed him more than anything," Byrd says. "Over the years, he really softened, and at the end, I do believe that he did go to heaven.

By Jason Kelly, a reporter for the South Bend Tribune in South Bend, Indiana with Catherine O'Connell-Cahill, associate editor of U.S. Catholic magazine. This article appeared in the September 1998 issue of U.S. Catholic.