The Claretian Martyrs of Barbastro.

When these words were written by Fr. Pérez, the Spanish Civil War had just begun; communist and anarchist forces were taking over towns and villages around the country. Both groups sought to eliminate Catholicism in Spain.

The Claretian Martyrs Museum, part of the Claretian House in Barbastro, Spain.

It was from this house in 1936 that Claretian priests and seminarians were taken to be martyred.

In July of 1936, an anarchist militia assaulted Barbastro, a town in northwest Spain which was the site of a Claretian seminary filled with young men preparing for religious life. On July 20th, the militia broke into the seminary; they claimed to be searching for hidden weapons, and were infuriated when they found none.

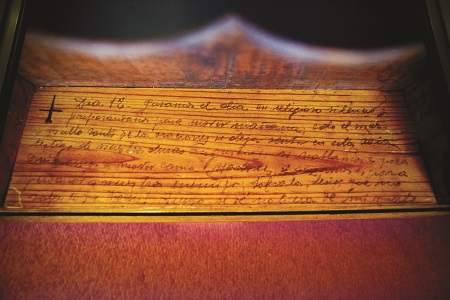

Last words, written secretly on a piano footrest, found inside of

the school where the Claretian martyrs were held before their execution.

The seminary’s Claretian Father Superior, Felipe de Jesús Munárriz, told the invaders there were no weapons and no politics on seminary grounds. He rang the bells to gather the community in the seminary patio. They all came, and remained silent and composed.

Fr. Munárriz and two other superiors were then arrested and taken from their Congregation that night. In the local jail and the relentless summer heat, the anarchists questioned the priests about the alleged weapons hidden in the seminary. One of the priests, Fr. Leonicio Pérez, held out his rosary to his captors, saying, “I do not have, nor do I want, any other weapon than this.”

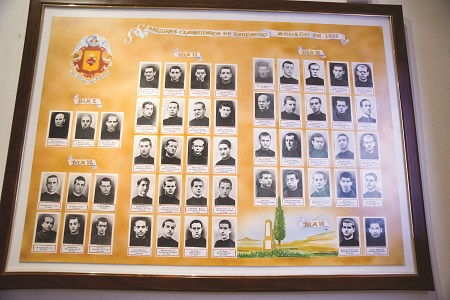

Photos of the 51 Claretians executed in 1936.

After almost two weeks of interrogation, the three priests, along with other prisoners, were bound and taken to the town cemetery late at night. There, lined up against an old adobe wall, they refused to abandon their faith. For their devotion to Christ, they were executed.

While the superiors had been taken to their interrogations, the remaining priests, brothers, and seminarians were tied up and marched in an ominous procession through the town. The men were confined in a school basement, certain they were awaiting their deaths. For 25 days, they were denied basic necessities, were taunted about their faith, and threatened with the goal of them abandoning their vows out of fear. The Claretians wore their cassocks throughout the ordeal as a sign of their fidelity to their Congregation and their faith.

Even in this horrific reality, the Claretian spirit prevailed. The men supported each other and focused on their community life with the Eucharist. They celebrated the sacrament daily with hosts hidden in their food baskets from outside supporters. They prayed and meditated in preparation for martyrdom.

The carefully preserved remains of 49 of the 51 Claretian

martyrs in the crypt beneath the Martyr’s Chapel in Barbastro.

The Claretians wrote messages of faith during their last days in confinement. Prayer books, scraps of paper, stair steps, walls, benches, and stage props were covered with their writing. They left stunning farewells and expressions of their joy at facing martyrdom for Christ.

On August 12, the revolutionaries summoned the six oldest of the imprisoned Claretians in the middle of the night. They were taken to the cemetery to face the same execution as their Father Superior and the others before them.

One of two memorial sites outside Barbastro; this

commemorates the site of most of the executions.

Three days later, the remaining Claretians were roused from their sleep. As they were bound in the same ropes used to tie up their fellow Claretians just days before, the young seminarians forgave their captors. Leading up to this moment the Eucharist, prayers, meditation, and writing had given the Claretians strength. Together, they had made their last confessions and encouraged one another to stand strong to the end.

“We have spent the day in religious silence,” wrote their leader, Fr. Faustino Pérez, “preparing for our death tomorrow. Only the holy murmur of prayers can be heard in this room, a witness to our deep anguish. When we talk, it is to encourage one another . . . .”

On their way to the field outside of town, the Claretians were mocked and beaten as they sang songs of Christ the Savior. There, they were offered a last chance to abandon their faith and pledge allegiance to the revolution. Some on their knees, others with their arms extended to the form of a cross, they shouted, “Long live Christ the King! Long live the Heart of Mary!” Gun shots silenced their final statements of love for Christ.

A painting inside of the Heart of Mary Church in Barbastro, Spain,

commemorating the martyrdom of 51 Claretian priests and seminarians

in 1936. In 1992, the martyrs were beatified by John Paul II.

The Claretians were buried in a mass grave in Barbastro and later identified by the names on their cassocks, which had been always sewn in by the tailor at the seminary. Simple monuments now occupy the places of the Claretians’ martyrdom in Spain, and the remains of the 51 men are kept in the church of Barbastro.

Pope John Paul II beatified the Claretian Martyrs of Barbastro in 1992; their feast day is celebrated on August 13. In his beatification homily, the Pope said, “Had these young men of Barbastro not received adequate religious formation and been trained in solid piety, they would not have merited the grace of martyrdom. Faithful to Christ, they triumphed with Him.”