Music

Marry Me

Marry Me

St. Vincent (Beggars Banquet, 2007)

Marry Me, the first album from St. Vincent, takes the listener from one extreme to the other. Most of the music is light and jazzy, but the lyrics are laden with images of violence, war, revenge, and uncertainties.

St. Vincent is the solo project of Annie Clark, a 25-year old multi-instrumentalist who has played with choral symphonic rockers Polyphonic Spree and toured with indie folk-rock artist Sufjan Stevens. Clark takes this cheerful and innocent background and throws in her own dark impressions of the world. Just looking at the album's song list displays the theme of destruction: "Paris is Burning," "The Apocalypse Song," and "Landmines" are three tracks.

One of the strongest songs on the album, "Paris is Burning," brings the listener straight to France during the world wars. The pounding lyrics-"We are waiting for a telegram to bring us news on the war"-recreate the tense and fearful wartime atmosphere of then and now.

Clark loves contrasts. Half of the songs on the album are smooth or peppy, featuring piano, stringed instruments, and even a children's choir. The other half are dark, with strong bass lines, and often end with a cacophony of sounds.

Clark, a former Catholic, gives no reason for taking the name St. Vincent. The question is posed: Is she a saint or a sinner? The title song is the sweetest song on the album. She croons for "John" to marry her, but what she really wants is to "do what married people do" and then to leave him.

Clark is clever in her criticism of religion in "Jesus Saves, I Spend." The lyrics argue that while Jesus is saving, we are wasting our time buying Christmas toys. She is also critical of sitting in the background and "sculpting menageries of saints" instead of being out in the world.

Whether the music is holy or sinful, Marry Me has an attraction that is hard to shake.—Kristin Peterson

My Name is Buddy

My Name is Buddy

Ry Cooder (Nonesuch, 2007)

In the age of the 99-cent digital download, the concept of an album, much less a “concept album,” may seem a bit passé. So here comes Ry Cooder with My Name Is Buddy, a 17-song fable that is not just a concept album but something approaching a roots-rock opera. The story follows a red cat named Buddy on his Dust Bowl migration in the company of an amphibian preacher named the Rev. Tom Toad. The illustrated CD booklet fills in the story around the songs.

Buddy’s subject matter is at least as unfashionable as its delivery vehicle. Today the unionized percentage of the U.S. workforce is in single digits, yet Cooder has concocted a tale about the union-organizing drives of the Depression through songs that invoke the names of Joe Hill and Paul Robeson, and dare you to look them up.

But then Cooder has never been in step with the times. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, while his peers were going psychedelic, he made antique-sounding albums of American country- and blues-derived music. Then Cooder veered off the pop path entirely, collaborating with obscure old masters from Hawaii, India, and Mexico. Eventually one of those collaborations, with pre-Castro Cuban musicians, struck gold as The Buena Vista Social Club.

My Name Is Buddy is the first album of original songs by Cooder in two decades. And, like many people, as he’s aged, Cooder has simply become more like himself. His roots music has grown rootsier and his growling vocals growlier. The music here blends the sounds of old-time string bands with gospel quartets and gutbucket blues to make a glorious, clanking cacophony that rumbles along behind lyrics about a little cat’s struggle for a place in the sun.

But My Name Is Buddy is not all anachronism all the time. For instance, in “Red Cat Till I Die,” Buddy sings, “won’t fight a rich man’s war and kill poor folks for you,” a sentiment that has become all too timely.—Danny Duncan Collum

Boys and Girls in America

Boys and Girls in America

The Hold Steady (Vagrant Records, 2006)

One side of the rock tradition (call it the Church of Elvis) is Southern, Protestant, and tormented by the contradiction between Sunday morning and Saturday night. But another rock denomination is Northern, urban, and Catholic. It starts with Dion (DiMucci) and the Belmonts and runs on down through Bruce Springsteen and Patti Smith. That Catholic rock tradition continues today in the person of The Hold Steady singer-songwriter Neil Finn.

Like many of the other Catholic rock artists, the 33-year-old Finn is lapsed in practice but still possessed by a distinctly Catholic sacramental vision of life in which the sacred is embodied in the temporal, and men and women are forever groping after that elusive point of connection between the two.

On Boys and Girls in America, The Hold Steady honor great Catholic rockers with their mainstream ’70s sound that seems to blend Bruce Springsteen and Thin Lizzy. On this album Finn is also inspired by two great Catholic American writers—beat novelist Jack Kerouac and poet John Berryman (who died in the band’s hometown of Minneapolis).

The album’s title, and recurring theme, comes from Kerouac’s line, “Boys and girls in America have such a sad time together.” And do they ever, in these songs, as they chase transcendence in a bottle, a bag of mushrooms, or a boyfriend, and remain “inconsolable because we can’t get as high as we got that first night.” Meanwhile Berryman’s last flight off the Mississippi River bridge gets the last half of the album’s opening track, “Stuck Between Stations.”

I wouldn’t give Boys and Girls in America to anyone under 18. Its romantic vision of wasted youth is far too compelling. But any listener with a few miles on the odometer will be floored by the deep and tragic vision in these happy songs about sad people.—Danny Duncan Collum

The Sermon on Exposition Boulevard

The Sermon on Exposition Boulevard

Rickie Lee Jones (New West, 2007)

Rickie Lee Jones is 52 years old now, the mother of a teenaged daughter, a sober political activist, and spiritual seeker. Her new album is dominated by a raw, aching spiritual hunger—and some equally raw guitar sounds.

For most people, Rickie Lee Jones is frozen in time as the hard-living twentysomething in the beret who had the hit, “Chuck E.’s in Love,” then faded away. Of course, she didn’t really fade away. For a while she veered off into jazz—a sure way to lose a mass audience. Then motherhood happened. Like many artists of her generation, Jones was shocked back into action by the Bush administration, and The Evening of My Best Day (V2 Ada, 2003) was a carefully planned and crafted return to form.

But The Sermon on Exposition Boulevard was an accidental album. Jones’ close friend Lee Cantelon is a visual artist who published The Words, a topically-arranged translation of the words attributed to Jesus in the gospels. In 2005 Cantelon was compiling an audio version of The Words over a droning acoustic guitar and percussion backing track, and Jones was one of his readers. But then, mid-session, she dropped the book and began singing variations on the gospel texts. Four of the tracks on Exposition Boulevard are from that session. These include the album’s opening and closing songs (“Nobody Knows My Name” and “I Was There”); “Where I Like It Best,” which paraphrases Jesus’ teachings on prayer; and “Donkey Ride,” which is, of course, a meditation on Palm Sunday.

Later Jones wrote and recorded eight more songs with related lyrical themes (including the directly gospel-based “Gethsemane” and “Lamp of the Body”) and compatible low-tech guitar-based backing tracks. The result is a thrilling indie-rock gospel album for people who think, but may or may not believe.—Danny Duncan Collum

Nashville

Nashville

Solomon Burke (Shout Factory, 2006)

In the 1960s Solomon Burke emerged as one of the greatest male rhythm and blues vocalists of the decade—and that’s when Otis Redding was still alive. Unlike Redding, Burke survived those years and ever since has been billing himself as the King of Rock and Soul, and acting the part in a regal, ermine-trimmed robe.

The coming of disco and hip-hop ended Burke’s days on the charts. But he enjoyed an artistic renovation after his 2001 induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Burke’s first album of this century, Don’t Give Up on Me (Epitaph/Ada, 2002), was produced by gen-X singer-songwriter Joe Henry. It featured songs by Bob Dylan and Elvis Costello and won a Grammy for Best Contemporary Blues Album.

With his new album Nashville, he takes on the country category, and the result is a soul-stirring collection that exposes the shared roots of all-American popular music.

Burke went to the Nashville home studio of alt-country guitar-god Buddy Miller and recorded songs by mainstream Nashville hit-makers (George Jones, Dolly Parton, and others), along with a few by country left-fielders such as Gillian Welch, Patty Griffin, and Miller himself. The instrumental sound is roots country—lots of acoustic guitars and pedal steel, some dobro and fiddle. But Burke’s vocal style is, as always, pure African-American gospel.

Burke’s getting older, but his instrument is only getting better. His version of Tom T. Hall’s “That’s How I Got to Memphis” is the saddest thing I’ve heard since the days when “Rainy Night in Georgia” was on every jukebox in the South. Burke’s cracked, resonant baritone is the sound of a man carrying an unmeasurable load of pain and bearing it with insurmountable dignity.

This is soul music, whether it’s backed by a church organ, a roadhouse horn section, or a country fiddle. And Solomon Burke is its rightful king.—Danny Duncan Collum

Sacred

Sacred

Los Lonely Boys (Sony Music, 2006)

From the Spanglish mash-up of their name and their lyrics, to the music’s uplifting fusion of blues guitar, R&B horns, and conjunto accordion, Los Lonely Boys are an American band for the 21st century. You first heard them in 2004 when their inspirational single “Heaven” and a self-titled CD hovered near the top of the pop charts. Now they’re back with a second album that proves the twentysomething Garza brothers, who comprise the band, are nobody’s one-hit wonder.

Henry, JoJo, and Ringo Garza are San Angelo, Texas Chicanos who cut their musical teeth backing their father, Enrique, a conjunto and country-western singer who moved his family to Nashville with hopes of following fellow tejanos Freddie Fender and Johnny Rodriguez onto the stage of the Grand Ole Opry.

Enrique Garza never made it big, but his boys did, playing music that owes as much to the late Texas blues guitar wizard Stevie Ray Vaughn as it does to any of their father’s training. The Lonely Boys’ big break came when they were discovered by septuagenarian country singer Willie Nelson, a fellow Texan who took them on tour and let them cut their first album in his studio. On Sacred, Willie, along with Lonely father, Enrique Garza, takes a verse of the song “Outlaws.”

For the 2 million people who bought the first Lonely Boys album, Sacred will hold no great surprises. It features the same ingredients of virtuoso guitar licks, Latin-flavored rhythms, easy-going pop tunes, and sweet fraternal harmony vocals, with the addition of occasional horns and a squeeze box. The lyrics of songs like “Diamonds” (as in “I ain’t got no...”) and “My Way” (“Don’t tell me how to live my life, don’t tell me how to pray...”) are so-so but complement the spirit of the music, which is uplifting and life-affirming. Los Lonely Boys are definitely here to stay. —Danny Duncan Collum

Colorblind

Colorblind

Robert Randolph and the Family Band (Warner Brothers, 2006)

The one-line blurb on Robert Randolph and the Family Band could be, “Sly and the Family Stone, without the drugs.” The music of this black-led, racially-mixed ensemble leaps out of the speakers with a cacophonous celebration of human possibility and hymns to the spiritual power of love. It’s one big party from beginning to end.

Guest artists—including Dave Matthews, Eric Clapton, and R&B singer Leela Moore—walk in and out of the room, amid overlapping voices and rhythms that demand that listeners throw their hands in the air and move. The lyrics of the opening track, “Ain’t Nothing Wrong with That,” update Sly’s ode to everyday people, promising to reconcile “break dance and slam dance...tight fade and long braids,” as well as “red, yellow, black, and white.”

But here’s the twist, at the center of this musical tent meeting is the pedal steel, an instrument usually associated with country and western music—and white people. But Randolph is a young black steel guitar virtuoso from a tradition called “Sacred Steel.” He grew up in a House of God holiness church in New Jersey. For the past 60 years, the steel guitar has been the instrument of choice at House of God churches from Jersey to Florida.

Young Randolph and his band jumped the confines of the church several years ago. They have collaborated with the North Mississippi All Stars and toured with the Dave Matthews Band. But they still get reviewed in Christian music venues, and their songs share a positive, life-affirming message that becomes explicit in “Love Is the Only Way In,” “Thankful and Thoughtful,” and the old Doobie Brothers chestnut, “Jesus Is Just Alright With Me.”

But the real miracle here is the roaring, soaring arsenal of sound Randolph produces from his steel and the depth and texture of the band arrangements. It’s an uplifting uproar.—Danny Duncan Collum

Modern Times

Modern Times

Bob Dylan (Columbia Records, 2006)

Bob Dylan is old enough to be selecting his Medicare prescription drug plan, but he’s nowhere near retirement. In fact for the past nine years he’s been on an artistic roll that’s produced his three best albums since the 1970s.

On the newest, Modern Times, Dylan produces himself for the first time with the band that’s backed him over several years of endless touring. In Dylan’s vocals you can hear the resonant rattle that’s entered his sixty-something voice, and the band delivers credible versions of rockabilly, Chicago blues, 19th-century waltzes, and the other elements of the vast roots of Dylan’s musical palette.

And that’s the great revelation of the re-born Bob Dylan: He is today exactly what he was 46 years ago—an American folk musician. In between he was a psychedelic prophet, a born-again Christian, and an Orthodox Jew. He’s been published in poetry anthologies and nominated for the Nobel Prize in literature. But he’s never been at home without a guitar around his neck.

Dylan recently settled the religion question, saying, “I believe in Hank Williams singing ‘I Saw the Light.’ ” And that sums it up. Dylan’s faith is in the swing and moan of America’s country and blues traditions, and a vision of life that is equal parts carnality and transcendence. On Modern Times, Dylan serves that vision up whole. The line, “Someday I’m gonna stand beside my King,” rests alongside a double entendre about some sugar in the bowl. In one song we meet the angel by the empty tomb, and in another a dirty old man lusts after the twenty-something R&B singer Alicia Keys.

The cutting-edge website, Pitchfork Media , recently called Dylan “the last American hero.” He’s certainly turning into one of them.—Danny Duncan Collum

Big Iron World

Big Iron World

Old Crow Medicine Show (Nettwerk, 2006)

Old Crow Medicine Show (OCMS for short) consists of five twenty-something white guys who play banjos, fiddles, and other acoustic string instruments. So, you’re thinking, here come the next bluegrass prodigies, chasing Alison Krauss and Nickel Creek. Wrong.

OCMS plays music older and funkier than bluegrass. They go back to the jug bands that played on street corners in the days before recordings. Unlike bluegrass, this tradition is biracial; the Mississippi Sheiks are as important as Appalachian banjo basher Uncle Dave Macon. In fact, OCMS makes us remember that the banjo was originally an African instrument and a staple of early African American jazz bands.

On Big Iron World, OCMS plays a string band version of the rhythm and blues classic “Down Home Girl” and a couple of traditional jug band songs. But their originals are just as deeply rooted as the covers. They play Woody Guthrie’s “Union Maid” and they wrote a song called “James River Blues,” about a Virginia boatman put out of work by the railroad (the “big iron” of the title). And both songs make perfect sense in this post-industrial Wal-Mart century.

Traditional American music has always wrestled with injustice, and with sin and redemption. OCMS has that covered, too. There’s an original gospel tune called “God’s Got It.” But the high point of the album is “I Hear Them All,” a Whitmanesque incantation in which the singer hears “the lowliest gathered in their stalls . . . the flowers growing in the rubble of the towers . . . the lamb of Judah sleeping at the feet of Buddha”—and pulls them all together in a mystic vision of unity.

Listen to Big Iron World a few times, and you’ll start to wonder if perhaps the best rock ’n’ roll band in America today plays without a drummer.—Danny Duncan Collum

The true false identity

The true false identity

T Bone Burnett (Sony, 2006)

T Bone Burnett entered the rock history books in 1975 when he left his Fort Worth, Texas home to play guitar behind Bob Dylan on the legendary Rolling Thunder Tour. In the 1980s he made a series of underappreciated solo records, but The True False Identity is his first work as a recording artist since 1992.

During that long interval, Burnett became one of America’s most important record producers. He midwifed early albums by Los Lobos, Counting Crows, and the Wallflowers and one of the very best ones by Elvis Costello (King of America), among many others. He also created the soundtrack album for the film O Brother, Where Art Thou?, which created a new audience for old-time and traditional American music.

As a producer, Burnett is all about the artist. The only thing his production jobs have in common is a clean, crisp, organic sound. So, of course, his return as a recording artist features harsh guitar sounds (from Tom Waits’ sideman Marc Ribot) and lots of rumbling percussion. The True False Identity boils all of Burnett’s roots and music influences down into a bubbling and smoking 21st-century stew.

And the sound fits Burnett’s thematic concerns. In “Fear Country,” he sings sardonically about the president: “Cowboy with no cattle, warrior with no war. They don’t make impostors like John Wayne anymore.” On “Blinded by Darkness,” Burnett, who has never made a secret of his Christian faith, rails against the Religious Right. “Do we really want to inject the concept of sin in the Constitution?” he asks. The song closes, “In seven days, God created evolution. When shall I expect retribution from the counterrevolution?”

After all these years, T Bone Burnett, the singer-songwriter, may finally be finding his time.—Danny Duncan Collum

Gold brick

Gold brick

Jon Langford (Roir, 2006)

In three quick decades Jon Langford has gone from helping invent punk rock with his old college band The Mekons to performing, on his most recent solo album, an earnest, gutsy cover of Procol Harum’s interminable sea chanty, “Salty Dog.”

A long, strange trip, indeed, but it gets stranger. He also has moved from Leeds, England to Chicago, fronted a country-rock bar band (the Waco Brothers), and developed a thriving career as a painter of cowboy pictures. Meanwhile, the Mekons, who still reunite every few years, added a fiddler and accordionist, and recorded an album of “electronica” dance music.

Langford’s brilliant career defies easy summary. But for the uninitiated, Gold Brick is as good a place to start as any. A literal love affair brought Langford to Chicago, but since then another has blossomed with country music, and this new album continues the romance. With their lilting, folk-derived melodies floating on waves of piano and violin, these 12 songs are certainly the most accessible work of Langford’s career. In other words, the album bears not a trace of the singer’s punk rock origins. But it does, like his other solo work, give us a direct look into the soul of a displaced English socialist in love with his new country and simultaneously baffled and enraged by it.

The album cover bears the subtitle “Lies of the Great Explorers or Columbus at Guantanamo Bay.” Those political themes are expressed with subtle irony in “Gorilla and the Maiden” (a King Kong tale in which “a hundred investors in hairy suits paw at a city served up in chains”) and the migrant’s tale, “Dreams of Leaving.” But the closing track, “Lost in America” (composed for the National Public Radio show This American Life) is more typical of the Langford catalog, as it swings through a rock-hard version of American history from Columbus to John Henry to Abu Ghraib.—Danny Duncan Collum

Living with war

Living with war

Neil Young (Reprise Records, 2006)

It may not end the Bush presidency, but Neil Young's album Living with War and its most famous song, "Let's Impeach the President," will certainly go down as the pop music event of 2006.

The album was recorded in three days in April and released instantaneously on the Web. Its nine original songs declare the state of the nation in urgent declarative sentences ("America needs a leader") sung to folkish melodies over Young's patented wash of distorted electric guitar and lumbering bass-and-drums thud. The 10th song is a version of "America the Beautiful" sung by a 100-voice gospel choir.

If nothing else, Young has proven that rock 'n' roll can still throw annoying bricks through the windows of American culture. "Let's Impeach the President" says things no one in the political mainstream will say quite so baldly. Its verses call George W out for lying and spying and name his White House staff as a bunch of criminals, but the enduring power of those loud guitars and drums allows Young to cut through the media clutter and be heard.

Living with War also is an astounding testimony to Young's artistic longevity. It's been 40 years since his first band, Buffalo Springfield, hit the charts with another topical anthem, "For What It's Worth." You'd have to go to novelist Philip Roth or filmmaker Robert Altman to find an American artist who has remained current over such a long period. One of Young's best acoustic albums, Prairie Wind, and the Jonathan Demme concert movie it inspired (Heart of Gold) were still in active release when he unleashed Living with War. And Young's savvy use of the Internet as an artistic and political vehicle could more befit someone half his age.

On his 1979 album Rust Never Sleeps, Neil Young sang, "It's better to burn out than to fade away." Almost three decades down the line, he shows little sign of doing either.—Danny Duncan Collum

The real deal

The real deal

Billy Joe Shaver (Compadre, 2005)

After 40 years in and around country music, The Real Deal by Texas singer-songwriter Billy Joe Shaver is either the capstone of a checkered career—or the beginning of an improbable third act.

The first of Shaver's two previous brushes with fame came in the early 1970s when country music outlaw Waylon Jennings recorded Honky Tonk Hero, an entire album of Shaver songs. But all the money went up in drugs and alcohol, and Shaver almost did, too.

During Shaver's second act, he led a band that featured his son Eddie on lead guitar and appeared in the 1997 film The Apostle. This era came to a crashing halt when, within a year, Shaver's son died of a drug overdose and his wife of 40 years died of cancer. These tragedies inform several songs on The Real Deal.

The full range of Shaver's art is displayed on this newest album with sparse guitar, bass, and drums that place the songs, and Shaver's evocative croak of a voice, front and center. There's "Aunt Jessie's Chicken Ranch," a cowboy ballad that could be the soundtrack to a Cormac McCarthy novel. There are grown-up love songs and losing-love songs, and there are rollicking novelties such as "Slim Chance and the Can't Hardly Playboys."

But the heart of the album is found in the songs that overtly express Shaver's hard-won, down-home mysticism. "Jesus Christ Is Still the King" could be a conventional gospel sing-along, but then it hits you with these lines, "When I found my life was lost/In my heart I carved a cross/And sealed it with a song I lived to sing." In "Try and Try Again," a testimony to personal salvation evolves into a utopian vision in which "the fighting will be ended and all hunger will be gone" and "our point of view is gonna grow into a pure and perfect one."

A Texas roadhouse might be the last place you'd look for revelation. But here it is.—Danny Duncan Collum

Electric blue watermelon

Electric blue watermelon

The North Mississippi Allstars (ATO Records, 2005)

The world of commercial pop music is youth-oriented and globalized, the aim being to synthesize a recording that every 16-year-old on the planet will buy at the same time. But far, far beneath the strip-mall surface of 21st-century pop is a barely-living core of tradition. It's the sound that happened when the kidnapped peoples of West Africa banged into the Anglo-Celtic culture of the American South. The contemporary pop music industry was born in the 1950s and '60s when that sound acquired the global megaphone of electronic media. In most pop music today it's impossible to hear any living connection to that old tradition, rap music being the exception.

Then there are the North Mississippi Allstars—a three-man-band of two white brothers and their African American childhood friend, bassist Chris Chew. The brothers, guitarist Luther and drummer Cody Dickinson, are the sons of the legendary pianist and producer Jim Dickinson who was part of the '60s Memphis folk scene and went on to do session work with the Rolling Stones, among others.

The Dickinson boys started out in punk and rap-rock bands. As they've matured, they've integrated their firm foundation in North Mississippi Hill Country blues. The Allstars now make music that transcends generations. Guest artists include rappers (Memphian Al Kapone), septuagenarian bluesmen (Othar Turner and R.?L. Burnside), and a middle-aged country singer (Lucinda Williams). Electric Blue Watermelon includes originals ("Moonshine," "Hurry Up Sunrise") in a Southern rock mode, hardcore funk ("Stomping My Foot"), and at least one traditional number, "Mississippi Boll Weevil," that's older than the three band members combined.

The Allstars are a living illustration of James Brown's comment, "Music is like water. I've never heard of young people's water and old people's water. There's just water."

Drink up.—Danny Duncan Collum

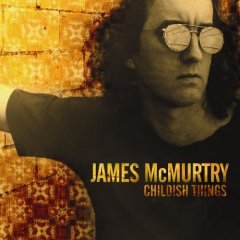

Childish things

Childish things

James McMurtry (Compadre Records, 2005)

Like his father, novelist and screenwriter Larry McMurtry (Lonesome Dove), singer-songwriter James McMurtry tells stories of small prairie towns and the lives they hold. James does it in tough, sharp-edged country-rock recordings. Childish Things is his most recent.

Until 2004 McMurtry never considered himself a political artist. His stories of rural life have always contained indirect social commentary. But then something snapped. After years of watching farms foreclosed and factories shut down, McMurtry let out a bitter roar of protest against corporate America and the Bush administration in the seven-minute song “We Can’t Make It Here.” In the song’s lyrics, McMurtry, through the voice of a laid-off factory worker, shows what happens when the economic heart is ripped out of a community.

McMurtry wrote that song in the fall of 2004, recorded it hastily, and put it on his website as a free download in the weeks before the last presidential election. In the following year he re-recorded the tune for Childish Things and deepened his political involvement by joining Cindy Sheehan and Veterans for Peace protesting at President Bush’s Crawford, Texas ranch.

Most of the other songs on Childish Things are McMurtry’s usual odd, thoughtful snapshots of everyday life. “Memorial Day” captures all the loopy chaos of family outings, and “Bad Enough” freezes that moment when a wandering husband stands on his doorstep afraid to go in.

But McMurtry’s album begins and ends with the war. In the first track, “See the Elephant,” two small-town boys see the coming of war as an adventure. In the last verse of “Holiday,” a tired, middle-aged Iowa Guardsman sits in his desert fatigues waiting for the plane that will take him back to Iraq for a second tour.

That’s life in the heartland these days, and James McMurtry won’t let us forget it.—Danny Duncan Collum